Roland. Brave, noble Roland. Count of Brittany. No, not that Roland. No, not

that Roland, either. And certainly not the one these guys are referring to, though

that’s a great song. As is

this, by another renowned artist.

Brother Roland in this instance is nephew to King Carlon; Holy Roman Emperor

(the First!) Charles; French King Charlemagne. You understand now.

From the moment I began my study

of the Dark

Tower

Series,

which is ongoing, I knew Roland was a special character. From the fairy

tales of Childe

Rowland, we can surmise him to be an adventurous youth yet sturdy in the

discipline of knighthood and battle and a representation of true chivalry,

putting violence aside in the name of his opponent’s life for the reward of his

family’s life. In the Stephen King

rendition, he is a gunslinger of incomparable skill. Peerless. His quest is somewhat

mysterious (we know it is to reach the Dark Tower, but where I am, I still do

not yet know why), yet remains

entirely noble throughout. In the dark, ghastly

poem of Robert Browning, Roland is as much a victim as a protagonist, and

though his name and slughorn can be tied to The

Song of Roland, his journey is more of a nightmare and what happens when he

conquers his quest is never truly revealed.

Roland, in most of these settings, remains a tragic hero. In

The Song of Roland, however, I get to

nerd out on Medieval bravery and complete lack of fear, where battle is the

prime source of gaining renown, and renown is how knights earn a living; and

knights such as a Roland, whom enemies and hordes of Paynims (Pagans) are out

to slay, look forward to epic battles, live or die, as a chance to firmly plant

their name as honourable knights.

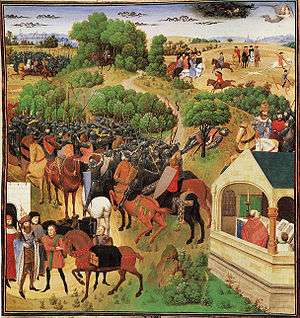

The plot is simple: Charlemagne’s

war with the Spanish Paynims drags on, and as he would much prefer to return to

France, he reaches a deal with their king, Marsilion. Carlon will cease warring

in France, as only the city Saragossa still stands, to send a legate to

Marsilion and ask for his baptism. His goal is to unite Europe in Christendom

(entire sixth through seventeenth century historical spoiler alert!). As the

last knights to deal with Marsilion on a diplomatic mission were executed, no

one volunteers for the mission. Roland, bravest and boldest and favourite

knight of Charlemagne, volunteers his step-father, Ganelon, also called Guénes.

A man furiously jealous of the King’s love of Roland already, not to mention

Roland’s skill in battle, is sent on this mission against his will. Spite,

self-preservation, and jealousy weigh heavy on his mind.

Once arrived at the foot of Marsilion, Guénes makes his move

and strikes his deal. Marsilion will be baptized, all of Spain will unite with

Charlemagne under Christendom, but it must be done in France. Absurd riches of

treasures from the Spanish king will help convince Charlemagne that it must be

done under Marsilion’s simple stipulation: that it honour the Holy Roman Empire

by being done on their soil. Ganelon adds that if he would wish to defeat

Charlemagne, he could do so by defending his honour and slaying his step-son

who sold him out to certain death by dealing with the same blood-thirsty Paynims

he happens to be selling the deal to. Lo, you are an elitist salesman, Ganelon.

It is not often one reads of an instance in which a diplomat visits a

combatants kingdom and tells them “I was nominated to visit you against my

will, under the apprehension that you filthy savages would gut me upon arrival,

so let us strike a deal for the sake of revenge upon he who nominated me for

this trip.” Entertaining treachery by Guénes, to say the least.

By the time the treasonous, traitorous, step-father to our

hero has left, he has set up Roland’s certain death. As King Carlon leaves for

home and resigns this war to peace, as part of Marsilion’s deal to be baptised

within the Roman Empire, Roland will no doubt be on the Kings rearguard through

the pass atop the Pyrenees. Ah, those dreadful Pyrenees.

Roland the Indestructible fights with the Twelve Peers,

Charlemagne’s best and favourite 12 knights. 10,000 strong of these valiant,

noble French vassals and princes fight for the Twelve Peers against the hordes

of Saracens, 150,000 total. Roland mentions to his friends, in the end, that

his uncle Charlemagne may see them all dead upon his arrival of the

battlefield, but he shall see no less than 15 dead Saracen for every Frank.

Roland’s stubbornness is part of the reason everything

unfolds. In a truly beautiful display of the Medieval stubbornness that

signified the onset of chivalric deeds, Roland refused to sound his Oliphant, a

horn of elephant’s tusk (hence the name), to alert Charlemagne and the majority

of the French army that they are under ambush. Not until nearly all are dead

does Roland blow the horn, his temples bursting and blood pouring from his ears

when he finally does, and much, much too late.

Of all the Christianity blowing the hell out of a good story

and making the poem seem like Christian propaganda to expel the world of the

evil that is the Muslim faith and its somehow perfect ally and equal, Paganism

(there are historical instances I will not reference here that involve Pagans

and Muslims teaming up against Christians, hence the view they are one and the

same from the Christian perspective in this story), there is still a very epic

Medieval story being told. And though it differs from some of the other majour

Middle Ages epics I read

and favour, there

are some things that stand out that make me love this book. Not just Roland’s

stubborn knighthood, either.

The characters, for example, are interesting. Not so complex

as you would prefer in a modern day epic, but enough to appreciate. Of the

Twelve Peers, three primarily are mentioned: Roland the Count of Brittany

(obviously); his best and most loyal friend, and not to mention wise and

level-headed Oliver; and the surprisingly crafty sword-wielding Archbishop

Turpin, who slays many a Saracen. They all have their say in the course of the

battle and it is very representative of their character, even if it goes

against what the ultimate knight Count Roland has to advise. Conflict like this

makes any story great, but seems to stand out in a story that takes place in a

time where killing in the name of your king/god was always the best course of

action.

Oliver is the primary dissenter when Roland refuses to sound

his Olifant (a horn made of ivory) to alert Charlemagne they are being ambushed

and outmanned 15:1; but when they commit themselves to fighting to the death for

the glory of their Kingdom and God, Oliver slays well. And when they are down

to a force of merely a few handfuls, still with hundreds of Saracens in front

of them, Roland decides it is time to sound that horn. Time to let Charlemagne

know the battle is lost, but the war can still be won by the Franks. Oliver,

however, now dissents to its sounding, swapping the sides of the conflict, and

his reasoning is just: You put it aside to spare your pride and assure us all

we would fight in glorious battle, and now that death looms near you would fear

what you have sentenced us to and use it to ask the King to come to our aid? Coward!

He will not be here in time anyway, may as well fight to the death and die

knowing you did not go back on your word.” (Not actual quotes, by the way).

His reasoning is sound. But Roland has another idea, which

is to sound it and let Charlemagne come – knowing they will die before he

arrives – to let him know that they died fighting Marsilion’s army and that he

should avenge their death. This is how it happens. And the ambush at

Roncesvillas ends with the death of every French soldier, knight, and prince.

But Roland dies a hero’s death, not slain by any Saracen but instead dying of

his own body giving out after such an exertion of inhuman strength. With

nothing left, especially after blowing the Oliphant until his temples burst, he

collapses and his soul is carried away by the angel Gabriel.

But soon enough, Carlon’s vengeance will return the favour

and it is swift, vicious, and non-discriminant. The Emir of Babylon, Baligant,

tries to catch Carlon off guard as the French spend the night with their fallen

friends and give the Twelve Peers a proper burial together. The plan, as

Ganelon had worked out for them, was that the French would be too shocked and

too emotionally distraught to fight properly, is a complete failure. The French

fight with a fire no one could have expected, and before too many can be

slaughtered, Charlemagne and Baligant knock each other off their respective

horses and square off in a sword fight. Once Baligant is slain, Saragossa falls

soon after and Marsilion’s queen, for he dies also in attempt to flee, is taken

back to France for a baptism.

Ganelon undergoes a trial, which seems a bit more civilized than

I expected of such bloodthirsty and emotional wrecks of knights under the Holy

Roman Emperor’s army. In this trial Ganelon convinces everyone that his

vengeance was only to have Marsilion defend his honour by getting back at

Roland for what he did to him by sending him out on the diplomatic mission,

thought to be certain death at the time. Though we know this not to be the

case, the court buys it. Until, that is, a young knight, Thierry, challenges

the knight defending Ganelon, Pinabel, in judicial combat. It is the equivalent,

in today’s sense, of the prosecuting attorney challenging the defense attorney

to mortal combat. The idea is that God will empower the side that is right and

grant him victory, which seems more representative of the times than that whole

fair trial bullshit. Young Thierry, against all odds and physically outmatched,

somehow defeats Pinabel. Ganelon, now proven

guilty, is given death by four horses pulling him apart, which separate

each arm and each leg in a gruesome public execution. As though this were not

enough to heal the pain that ails the King and his army, thirty members of the court

of Ganelon are hanged just in case they also have vindictive tendencies.

Truly Medieval, this epic: spectacular battles, violent and

stubborn, with great mourning for the brave knights that fall but never a

thought of relenting as death stares them down. No escape, but no desire to

ever try. The thought of turning back is more vile and vulgar than being cut

open, maimed, decapitated or any other gory death. That is part of the great

life and honour-code of knights that I enjoy when reading stories of the Middle

Ages. The exaggerations and emotional sensationalising that the story tellers

added to it never bothers me, though this book has that as much if not more

than any other I have read. Also, getting over the Christian element is

difficult. It is usually added to Medieval stories almost as an afterthought,

just to remind the readers (or listeners, when the story was first decreed) that

the good guys are indeed going to heaven, the king does indeed rule by the

grace of god, and the enemies are indeed heathens, infidels, Pagans, Saracens,

or some other word for Muslims and/or Polytheists. It is very typical of the

Middle Ages, but the Christian element is heavier in this one than in any other

I have read. And it is placed in such a way that it does not always fit. Still,

the debate amongst scholars rages on as to whether this was written as propaganda

for the Crusades (as some Crusade terminology is used) or as a precursor to the

Crusades, before Christians declared war on all those in the Holy Land.

Important as the Holy Roman Emperor is as a figure in human

history, especially the first one in King Charlemagne, I will still, for my money,

take a bold, battered war horse like Willehalm

in his epic, who travels to see the Emperor in person and literally slaps the

hell out of the Emperor’s wife, who happens to be Willehalm’s sister. Really

beats the hell out of her whilst trying to beat

sense into her. At times, picking her

up off the ground by her hair so he can beat her some more. Great stuff from a

veteran of the Crusades and former prisoner after capture before his escape

with the central figure of that story.

But, as far as this poem is concerned, it is an important

piece of literature undoubtedly. Referenced by nearly every other Medieval

story after it, as well as stories involving knight errantry and brave warriors

in later time periods (Don Quixote, for example), this story will always firmly

retain its place in the upper pantheon of Middle Ages Epics. So if you happen

to be into that sort of thing, like I am, then I say it is a must read.